ALACHUA COUNTY BICENTENNIAL POSTCARDS

The Writers Alliance of Gainesville brings moments from Alachua County’s 200-year history to life. These short pieces, inspired by postcards from the Matheson History Museum Archives, were written for the Museum’s juried online exhibition of “Alachua County’s Bicentennial Climate Story,” to be launched in December 2024.

Table of Contents

- Letter from an Orange Juice Lover, by Michelle Marcotte

- Sandhill Cranes: Courtship Dance, by Mallory O’Connor

- Phosphate Mining Comes to Gainesville, by Carol Mosley

- A Beautiful Tobacco Plantation in Florida, by Amber C. Lee

- An Editorial on Democracy, by Jenny Dearinger

- A Letter from a Young Southern Belle to her Favorite Cousin, by Barbara Bockman

- The “Ladies’ Club”, Melrose, Florida, ca. 1900, by Charlotte Porter

- Where is Our Home? by M.A. Hastings

- Bicentennial Wagon Train, by Sue Blythe

- Lament for Life Below Water, by Mary Bast

- 70,000 Young Tung Oil Trees in Nursery near Gainesville, Fla., by Pat Caren

- Pulling Turpentine in the South, by Michelle Dunlap

- Tapping Longleaf Pines for Turpentine, by Susie H. Baxter

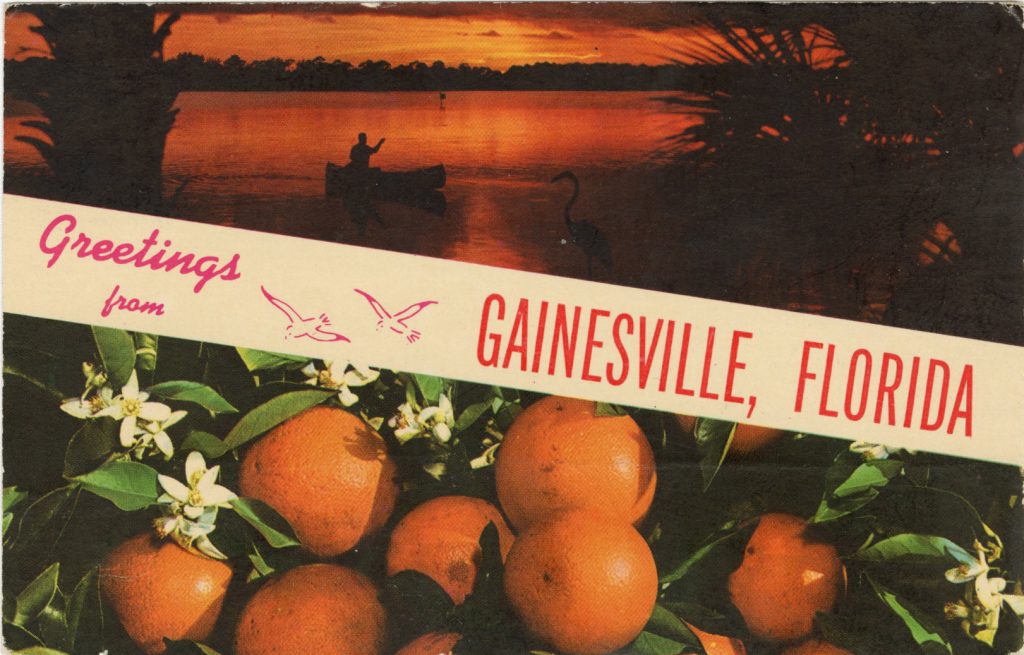

- Letter from an Orange Juice Lover, by Michelle Marcotte

Dear Citrus Farmers and Farm Workers. Thank you. You put your shoulders to the wheel of agriculture, lives spent in repeated cycles of plant and nurture, harvest and market. You picked yourselves up after hurricanes, battled diseases and continued to paint Florida orange. In doing so you fed the United States and elsewhere nutritious, delicious citrus fruits. Florida produces 70% of the citrus in the US. Florida is a giant in world citrus production, thanks to your hard work.

Thank you truckers, railroaders, distributors and grocers who moved the citrus to the markets, because without a market, without sales, there can be no growth. But trade is a two-edged sword. Citrus originated in China and spread via trade. Floridians adopted and adapted citrus and made it our own. But from China, from world trade, also came the psyllid, the tiny, lethal killer of citrus trees, the destroyer of production. It causes citrus greening a disease that has reduced citrus production by 30%, and higher, in Florida and worldwide.

Thank you research scientists, food scientists, technicians and extension workers who learned and then spread knowledge so citrus growing and farms could prosper. You conquered weather with hardly, cold-resistant plants, your frozen orange juice concentrate made orange juice possible for us all, you conquered diseases and pests. Citrus Canker Be Gone! Now can you please do the same with the psyllid that causes citrus greening?

Alachua County hosted a commercial orange growing sector until two years of back-to-back cold snaps killed the trees and the entire orange growing sector (twice in one-hundred years). So, we knew, before the rest of Florida, the harm of extreme weather on agriculture. And now, with climate change regularly causing damaging extreme weather we can advocate to prevent, mitigate and turn back climate change. And failing that, we will need farmers and research scientists to be ready to pivot to crops that will survive it.

Pull some magical knowledge out of your hats because upon all your backs stands the world’s growing population and our need for affordable food.

Cheers!

Orange Juice Drinkers Everywhere.

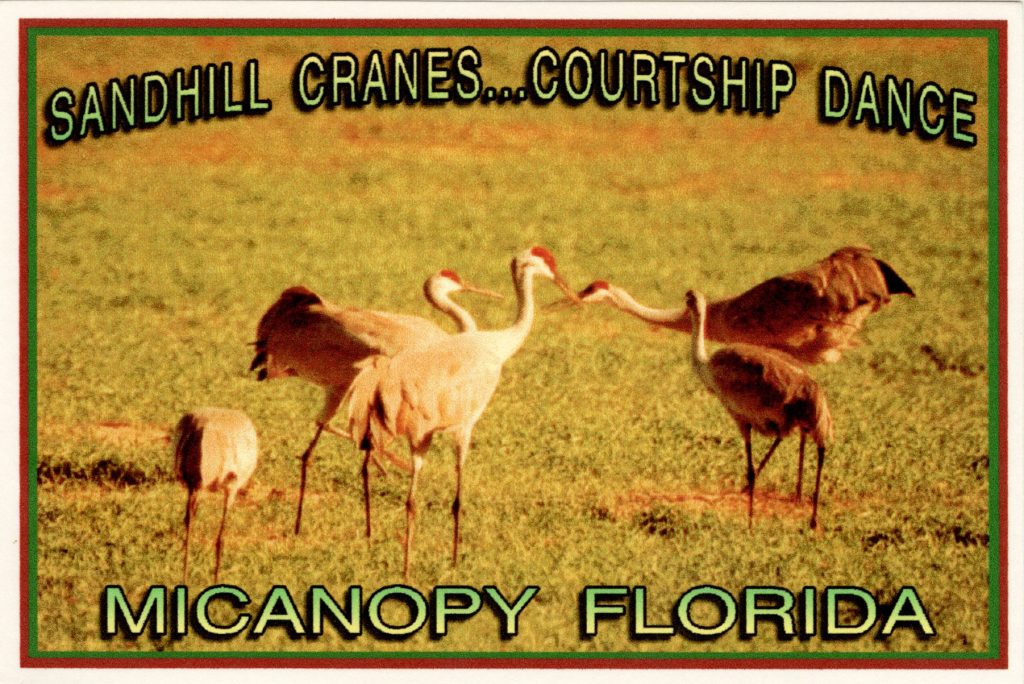

- Sandhill Cranes: Courtship Dance, by Mallory O’Connor

I heard them before I saw them—their distinctive plaintive cries wafting like a wave across the dry grass of my neighbor’s pasture. I stopped to watch, leaning on the fence rail.

They were a party of five—three adults and two youngsters who looked to be almost grown. My neighbor, Sam, had told me that the chicks, referred to as “colts,” stay with their parents for about a year before forming nomadic groups with other juveniles. I suppose we’d call them “gangs. But today they are models of decorum, walking alongside their mom, glancing around at the grassy landscape.

About 4-5000 cranes (Grus canadensis pratensis) live in Florida year-round. They are joined every winter by about 25,000 migratory cranes who make their summer homes in the upper mid-west before they head south to spend the winter. It’s been suggested that the cranes follow Interstate 75 the same way that other migratory birds follow major rivers., but that would be hard to prove. And the cranes are not likely to tell me if that’s true.

They’re closer now and I can appreciate how tall they are. An adult male can stand over six feet and their outstretched wings can measure six feet across. I recall that Sam told me that Sandhill cranes are among the oldest bird species on earth with fossil examples dating back at least two million years. They are also among the longest-living birds with an average lifespan of around thirty years. No wonder that in Asia they are revered as symbols of longevity and good fortune.

The five cranes were now just on the other side of the fence, so close that I could almost touch them. Then the largest of the group—the male I supposed—flung out his wings and made a purring sound. The two females turned toward him and responded with purrs of their own. Then, moving in what seemed an elaborate synchrony, they began to dance. Their magnificent wings closed and opened as they hopped and swayed, sometimes leaping off the ground entirely like ballet dancers in an exquisite pas-de-deux.

“That there’s their courtship dance,” said a voice.

I jumped and looked around. I had been so absorbed in the crane’s beautiful choreography that I hadn’t seen Sam’s approach.

“Them colts is about ready to leave,” Sam said, pointing. “Time to start a new family.”

I looked back at the pirouetting cranes. “So, does he have two wives?”

Sam laughed. “Not likely. That second female is probly just a friend. Them cranes, they mate for life, or so they say.”

I watched the cranes bow and leap, flying without leaving the ground. Slowly, one leap and skip at a time, they moved away, crossing to the other side of the pasture. Then, as though in some primordial slow-motion film, they lifted into the air and followed a spiral pathway into the evening sky.

Even after they disappeared into the clouds, I could hear them calling. . .

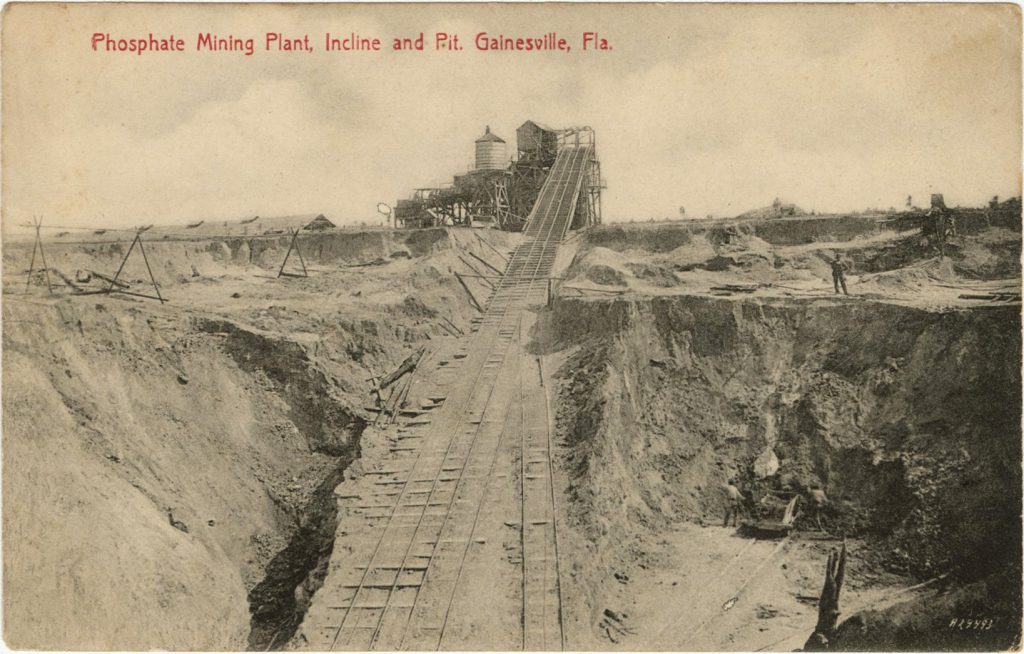

- Phosphate Mining Comes to Gainesville, by Carol Mosley

I was happy growing up on the farm. Sometimes I imagined going away to college, but I was mostly satisfied with my life as it was. And, after my chores were done, I was free to explore.

The land was fertile and mostly responded kindly to our nurturing. I understood the need for feeding the crops and one of my tasks was collecting manure. Nothing went to waste.

Don’t get me wrong. The work was hard and the weather unpredictable. I could see the worry on my daddy’s face when the rains didn’t come, or came too much. And, I tried not to let him know when I’d hear him ask for credit at Mr. Carter’s store. I could feel the shame in the sinking of his posture and pitch of his voice. He had no need for shame. Mr. Carter always gave him the credit. My daddy always paid his debts.

It was during one of those hard times when the decision was made to sell the farm and head for Florida. As we sat around the dinner table Daddy told us there was opportunity to be had digging for phosphate. This was not like the coal mines deep underground. No sir. This was in open quarries. I’d be sixteen soon, and we could work together for a better future for me. Maybe I could even go to college. I didn’t let on that I knew the bank was threatening to take the farm.

We arrived to Gainesville in 1901. We were hired straight away and issued pickaxes to go after the land pebbles that hold the precious phosphate rock. Cities needed massive amounts of food and wealthy landowners were getting into the agriculture business, controlling every step of the process. Turning phosphate into fertilizer could feed the world. Or so they said.

From what I could see, it looked like this phosphate rock was gonna feed some already stuffed pockets. The quarry was a wet mess and most of what was coming out was considered waste product. The men were coming home covered in rock dust, coughing violently to dislodge powder too fine to break loose from their lungs.

Over the next few years, when I could muster the strength after 12 hours working, I wrote to the Agricultural College in Lake City for information about this rock that was causing such a boon in land values. It turns out this stuff isn’t easy to come by, but new deposits are being discovered around Florida. Phosphate mining is becoming a big business.

The college is excited about the future of farming. I’ve got more questions. If phosphate is a limited resource, will we use it wisely so future generations have some, too? Will me and my daddy get sick like coal miners do? Who’ll clean up the mess created? If I ever get the chance to attend that college, I’m gonna find some answers.

- A Beautiful Tobacco Plantation in Florida, by Amber C. Lee

In the sweltering heat of a sticky Florida summer afternoon, an old, weathered postcard fell from a book onto the floor of Amelia’s grandparents’ attic. The postcard, yellowed by time, bore the title “A Beautiful Tobacco Plantation in Florida.” The image depicted an expanse of lush, green fields under a clear, azure sky, rows upon rows of tobacco plants stretching into the horizon, taller than Amelia stood herself. She picked it up, the image sparking a curiosity that led her down a path she could never anticipate.

Fast forward a few years, Amelia found herself amidst the very fields captured in the postcard, now a climate scientist, driven by a passion ignited by that accidental discovery. However, the scene before her was starkly different. The clear blue skies were now often enveloped and in a haze of pollution, the fields not as lush, and the workers wore masks to protect themselves from the dust and chemicals that filled the air. The beauty once captured on the postcard seemed a distant memory, replaced by the reality of a climate in crisis.

Amelia’s research focused on the impacts of climate change on agriculture, and the tobacco fields of Florida presented a poignant case study. Rising temperatures, unpredictable weather patterns, and increased incidents of pest infestations had taken their toll on the crop yields. The once thriving farms were struggling to adapt, their future uncertain in the face of these growing challenges.

Amelia discovered that the changes were not isolated to Florida. Similar stories were unfolding across the globe, with communities facing the daunting task of adapting to the rapidly changing climate. The realization was sobering, but Amelia found hope in the resilience of the human spirit and the innovative solutions being developed.

Through her research, Amelia advocated that urgent action was necessary to combat climate change and its impact for sustainable farming practices, not only in tobacco, but in all forms of agriculture. She spoke at conferences, published papers, and worked with local communities to implement changes that could mitigate the impact of climate change. Techniques like crop rotation, organic farming, and the use of drought-resistant plant varieties became part of the new approach to agriculture, aiming to restore balance to ecosystems disrupted by decades of exploitation.

Amelia’s work inspired others to take action, to look at the beauty of our world and recognize the urgency of protecting it for future generations.

Years later, another postcard was produced, this time capturing the same fields transformed by sustainable practices, a testament to the resilience of both the land and its people. The title read, “A Renewed Tobacco Plantation in Florida, Thriving Against the Odds.” It was a symbol of hope, a message that despite the challenges posed by climate change, through innovation, determination, and collective action, a brighter future was possible.

- An Editorial on Democracy, by Jenny Dearinger

All my life I equated democracy with freedom. The freedom to make choices; wear what I wanted; go where I wanted; the freedom to be me. My dad retired after 27 years of Army active duty as a Lt. Colonel in 1975. He enlisted at the end of World War II, got the GI Bill, and fought as a commanding officer in the Korean Conflict and the Vietnam War. He risked everything for me to live free.

But as I’ve gotten older, and the political climate has changed, my definition of democracy has become less naïve and more focused. My new definition is less about freedom than it is about maintaining and sustaining humanity. Democracy equals equality. Yes, I am a Democrat which is often associated with democracy, but during the Reagan years I was a Republican. As a Republican I would have done anything I could to defend democracy. I love the fact that I asserted my right and freedom of choice to move from party to party. I love the fact that I have tried to see issues from both points of view. My conclusion is that Democrats and Republicans want the exact same things, they just go about getting them differently.

Getting back to democracy, the planet is experiencing a population explosion. When I was born in 1963, there were 3 billion people on the planet. As of 2022, in less than 60 years (three generations), there are 8 billion people. By 2050, 70% of those people are predicted to live in cities. How can cities maintain transportation, infrastructure, jobs, provide healthy food and clean water, and provide safe homes for that many people? How can everyone on the planet be given an equal opportunity to be prosperous, healthy, and happy? In other words, how can we maintain and sustain a healthy and productive world?

Maybe I should talk a little about ‘omniscience.’ My definition of omniscience is seeing the whole picture; it’s seeing the forest rather than the individual trees. That’s how we maintain a sustainable planet for all. We take care of the big picture.

Some may say, “I just want to keep my own corner of the world safe and clean.” Ahh, if only! The problem with that attitude is that what happens to the planet affects (or infects) your little corner. A famine in Africa or the sea level rise in Australia puts strains on the planet’s resources. The people are forced to migrate, hygiene and health and hunger become issues, shelter becomes paramount. The place where the displaced people go becomes overwhelmed, financial markets are struck, and your corner of the world becomes involved.

Wouldn’t it be better to solve planetary problems before they become issues? Where do we start? In our own little corner, of course. I am so lucky to live in a democracy that gives everyone a right to vote. Voting is the individual’s way to make their opinions heard. Individually, we may not be able to make a difference, but collectively we can change the world!

- A Letter from a Young Southern Belle to her Favorite Cousin, by Barbara Bockman

My Dearest Cousin Nancy,

I am overjoyed that you asked me to be a bridesmaid at your forthcoming nuptials.

Mama and I chose the most elegant silk fabric for my dress; it’s a stunning shade of pink. Our

dressmaker, Hattie, will get to work on it right away. You might remember that Hattie is the

sister of my former Mammy, Bertha.

Of course, I don’t need a nursemaid now that I’m 14, so I chose one of the older ninnies

to be my companion. She’s Bertha’s daughter; the one who was born shortly before I was.

Don’t you think it’s funny that while Bertha was nursing me, her daughter had to be nursed by

another woman down at the quarters?

My new companion’s name is Jewels of Opar. Isn’t that insane? Bertha says she named

her for a flower that grows in Nigeria. I declare—how on earth she knows that I will never

know, but she always was one to tell outrageous tales.

Jewels of Opar is quiet and does my bidding without complaint, but I can see that I will

have to mold her into someone who will be congenial in white company. At least her skin is

very light. It’s such a chore trying to educate her to life inside the plantation house. Fortunately,

she has taken to hygiene! So that’s one item checked off.

Jewels is as chatty as her mama. And she repeats the stories that I’ve already heard

from Bertha. They love that tall tale that Bertha says her grandmother told her. I don’t know

where they get the gumption to say their great grandparents came to this country in leaky ships

and were chained in a space so small they couldn’t stand up. That just can’t be right. Mama and

I sailed to London in the most gorgeous ship. We even had a French chef who served absolutely

delicious dishes. I hope the story of slave ships will not be repeated, because it is just too

unpleasant to listen to. As Papa says, those disagreeable things should be buried. Papa knows

best about everything; Mama and I wouldn’t think of going against his wishes.

And, too, Papa says the Negroes here are very comfortable and are grateful to have a

good job and learn some skill. Papa instructs his overseer to be gentle with the workers.

Especially the women who have to carry heavy loads of cotton. He says Negroes have inferior

minds, so I recon I’ll have to be longsuffering when Jewels tries my patience. Bless her heart, I

can see she’s trying real hard.

Is it okay if I bring Jewels of Opar with me to your wedding? I hope to have her trained

to dress me by then.

Always, Your loving cousin,

Marilee

- The “Ladies’ Club”, Melrose, Florida, ca. 1900, by Charlotte Porter

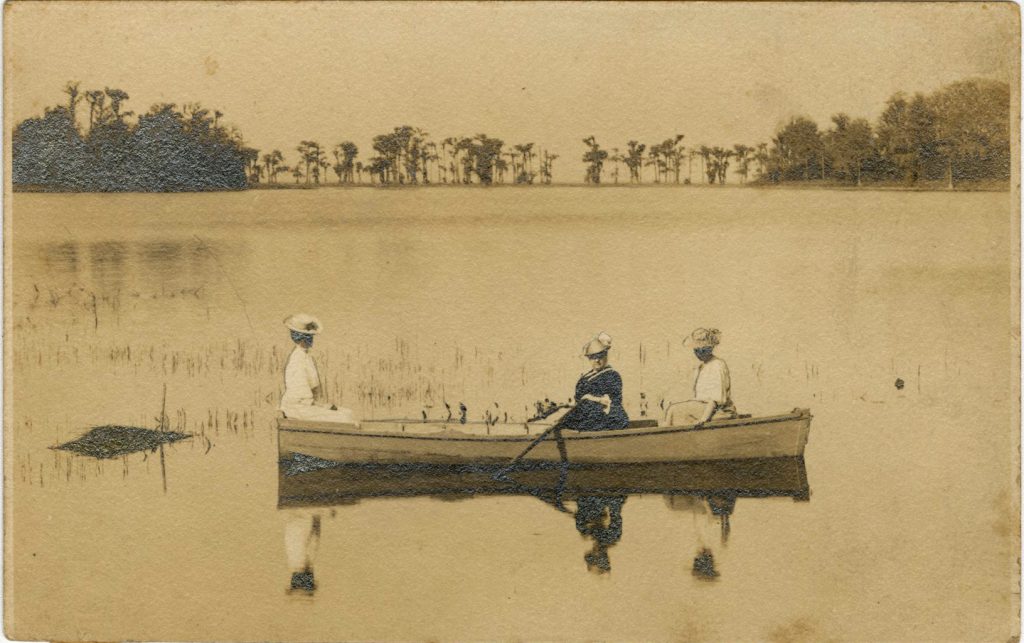

Afloat, at bay, this trio are members of the Melrose Ladies’ Literary and Debating Club. Founded in 1893, the group is one of the nation’s oldest continuous women’s clubs. The meeting hall stands near Pine Street. According to the minutes, education was a key issue in a community where residences were named for women.

The ladies pose in a john boat, a flat-bottomed skiff, popularized among northern readers by Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896) in letters published as Palmetto Leaves (1873). Stowe wrote for fellow snowbirds—women in white with wide straw hats or in grief’s dark mourning habit. Men, too, observed a boating dress code of white trousers, white jersey, vest, and top coat (permissible to remove when rowing).

In this photo, at oar, though facing forward, is Mrs. J [ulius?]. A. Remmel. From Pennsylvania, she and her husband built a waterfront house. Sitting in the prow is Miss Emma Tolles, presumably kin to Fremont and Clara Tolles, who, since 1888, wintered in Melrose in their Victorian “Montclare Cottage.” The town’s present museum was their packing house, and friends of the Tolles, the Tuttles and Baldwins, built residences in Melrose before the Great Freeze of 1894.

Fremont Tolles, a banker in Naugatuck, Connecticut, was on the forefront of change. By 1900, one in four Connecticut residents was an immigrant, and Naugatuck changed from a farming community to innovative industries producing Firestone’s first vulcanized rubber, Keds sneakers, Naugahyde, and, within a decade, Peter Paul candy, notably, the Mounds bar and Almond Joy.

Melrose was not hostile to foreigners or to new ideas. The town’s third mayor, Hans Felix Noszky, known as Baron von Noszky of Saxony, marshalled local resources and published important research on Native American history and an Indian mound on Etonia Creek.

So who is the unnamed woman sitting behind Mrs. Remmel? She might be a daughter of Nathaniel Orr and Elisabeth Holmes Orr, who winterized the “Home Acre” cottage in 1887. Elisabeth (1825-1909) was a poet and newspaper correspondent. Husband Nathaniel (1822-1908) was a brilliant wood engraver, established in lower Manhattan, New York. As a younger man, he engraved the illustrations for Twelve Years a Slave (1853) written by Saloman Northup (1807-1863) and dedicated to Harriet Beecher Stowe.

By 1881, goods, mail, and travelers moved from the Waldo train station to Melrose along a canal dredged from Lake Alto to Lake Santa Fe by a local company that issued 150 shares at $100 per share. Alas, the waterway, 30 feet wide and 5 feet deep, could not accommodate cumbersome commercial traffic, and Clara Tolles reported that the only steamboat caught fire in February 1884. The replacement tugboat Alert later sank. Pictured here is the City of Melrose, a cypress launch built by two enterprising locals, brothers Edwin and Bud Robinson. The launch remained in service from 1915 to the 1920s. A one-way trip took two hours because water hyacinth, introduced to Florida in the 1890s, clogged passage.

- Where is Our Home? by M.A. Hastings

It was the land of plenty

So way back then

That there are not even a few

Who

remember when

There was ever a thought about the pace of the renewal

Of the pine coned green longleaf

between

the White Two Legs and

the next of Their Kind’s face.

Yes, Deer SmallOne,

When slaking thirst was what

our ancestors panted to seek

they got relief at their laughing sisters,

Shallow Stream and Deepflow Creek

So dense was the biome

that was home

to our White Tail ancestral roam

That they did not know of

because they could not see

This blue sea now floating our biggest roofs away

from you and me.

The pine gum the

White Two Legs force

the Black Two Legs to drain out of

our Green Brother Trees gets turned into tar pitch

that then seals up the sides of

wooden boats and ships

Which

save them from sinking

under to

a watery grave ditch

If the lashed together logs make it downstream

They’ll turn into the homes of the White Two Legs’ dreams

And though that may seem

to some eyes

all good

What will happen

to your offspring

Deer SmallOne

now that gone

are our woods?

©️M.A. Hastings

- Bicentennial Wagon Train, by Sue Blythe

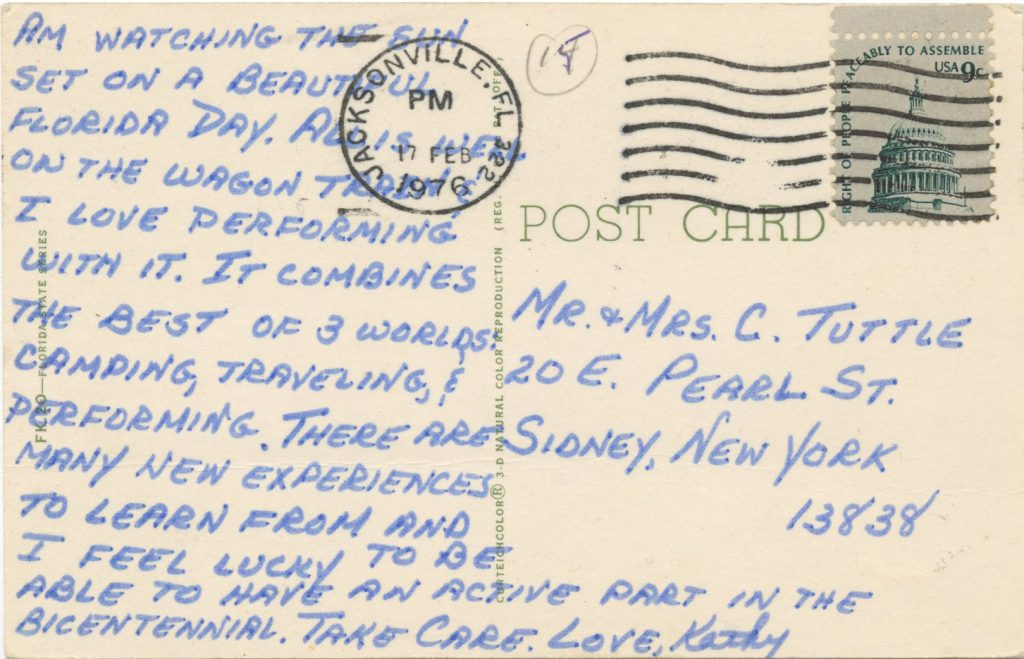

Kathy Tuttle leaned back, enjoying the sunset, the smell of the horses, the creaking of the webbed folding chair. She gazed at the Bicentennial Conestoga wagon and thought about the other 49 covered wagons making their way across the country. They would converge at Valley Forge, PA, not far from Philadelphia, where the Declaration of Independence had been signed on the Fourth of July, two hundred years ago.

Kathy wished she had more room on the postcard to her parents. How could she explain the magnitude of her experience in the Bicentennial Wagon Train? She was exhilarated and exhausted after the day’s parade and performance. Hawthorne was a small town, but hundreds of people of all ages came from Alachua and neighboring counties, on horseback and in horse-drawn buggies, carriages, and wagons, as well as by car and truck, to be part of the Bicentennial Wagon Train. She loved to hear the crowd sing along as the high school band played “You’re a Grand Old Flag” and “This Land Is Your Land.” They cheered when the traveling performers, in their pioneer costumes, sang “God Bless America” at the end of the program.

Kathy looked up. She watched two outriders galloping back from Gainesville, waving Bicentennial Rededication Scrolls. “Forty-seven signatures,” she heard the girl call as her horse settled into a walk. Kathy knew they would present the scrolls to the Wagon Master at the campfire that night. He would accept them with great flourish. Kathy wondered how many signatures they would have by the time they got to Valley Forge, PA. In this Bicentennial year, President Gerald Ford himself would sign the last Rededication Scroll that reads, “We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness…”

How could she say all that in the little bit of room left on the postcard? She shrugged and wrote, “I feel lucky to be able to have an active part in the Bicentennial. Take Care. Love, Kathy.” She went into the tent to get a stamp from her purse. Standing up in the glow of the sunset, she smiled at the motto on the stamp: “Right of people peaceably to assemble.” That was one of the many rights and freedoms enshrined in the US Constitution. She felt proud to be an American in this Bicentennial year. She licked and stuck the nine-cent stamp and tucked the postcard to her parents in her back pocket. She would have to wait til they got to the next town to mail it.

Kathy scanned the campground, looking for her husband. There he was, helping to build the campfire for the evening’s sing-along and hoe-down. She felt a deep-down, through-and-through happiness as she walked toward the next scene in her Bicentennial adventure.

- Lament for Life Below Water, by Mary Bast

“That I am part of the earth my feet know perfectly, and my blood is part of the sea.”

D. H. Lawrence, Apocalypse

A clean beach, quiet waves, a clear sky,

that’s how it used to be, the seas so stable

for a thousand years it seemed, reeds

swaying softly in the breeze. I saw my

granddaughter’s first toe-touch to the surf,

delight unfurled in joyous giggles and

a little dance inside the muted breakers.

Now I wake up to a warming world that rolls

so hot, so feverish, there’s no known antidote

to calm its fire. Oh, how disquieting, our

climate fast-forwarded beyond the actual years,

with no beach here in Florida that can escape

the ocean’s rise, eight inches higher since the fifties.

And imagine now ourselves as sea creatures, feel

the spacious ocean’s full reach and its heart beat,

know the rhythmic swish, swish among the plants,

animals, micro-organisms, rocking in the back and forth

of tides. Notice a subtle off-beat, signs and sounds

of eerie dissonance, the algae blooming wildly,

unintended crops that thrive on fertilizer run-off.

There are dead zones, too: we are befuddled,

instincts gone awry, strange currents now confusing

natural rhythms, neighbor fishes swim and swim

in circles, round and round until they die.

Nothing’s familiar, it’s so hot there’s more evaporation

from the surface and salinity is lowered.

Those dear sea urchins we see on Facebook

(wearing cowboy hats, sombreros, Mickey Mouse ears

in the laboratory tanks) are facing death

in their own habitat—these spiny little beings

cannot get a grip: righting responses, locomotion,

and adhesion lessened by the heat and lowered saline.

And the blanching coral reefs decline, as well,

the corals’ tiny larvae drifting, ciliary hairs

now cannot find familiar strumming fish or crackling

of snapping shrimp, their sound environment

no longer spelling home. As if the waters have turned angry

(and why not: we have destroyed a perfect haven),

just a hundred degrees Fahrenheit from boiling.

- 70,000 Young Tung Oil Trees in Nursery near Gainesville, Fla., by Pat Caren

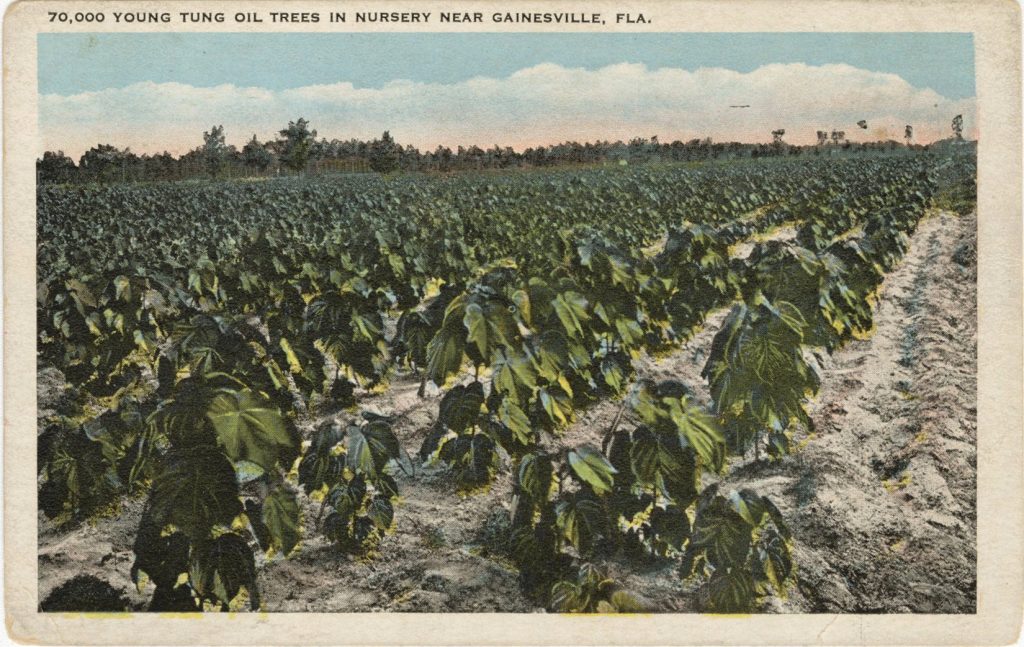

Tung trees (Aleurites fordii) are fast-growing deciduous trees native to China and Vietnam. They’re grown for their nuts, which contain high-quality, quick-drying oil used in lacquers, varnishes, paints, linoleum, resins, and other things. During World War II, the Chinese used tung oil for motor fuel.

In their natural environments, tung trees pose no problems, but in the southeastern US, they are invasive. Non-native invasive plants and animals tend to crowd out native flora and fauna. Some, mainly insects, carry diseases that can wipe out entire species. Chestnut trees and American elms, once widespread, were victims of chestnut blight and the Dutch elm disease. Recently, Florida’s red bay trees are in danger due to the ambrosia beetle and the disease it carries.

Invasive plants cannot replace natives in a healthy ecosystem. Our native insects seldom find non-natives palatable. That has been a selling point in the nursery industry, but birds need insects to eat. Birdseed doesn’t cut it. In order to produce babies, our avian friends require the protein and nutrients they get from a diet of insects.

Tung isn’t the only problem plant intentionally introduced into the US. Water hyacinth, camphor trees, Chinaberry, Japanese climbing fern, tree potatoes, Japanese honeysuckle, and mimosa trees are a short list of local plants brought in for beauty or utility. We tend to recognize the danger only after the damage has been done.

Even today’s gardeners are complicit in the introduction or spread of disease. Tropical milkweed is sold and planted widely, as it has beautiful flowers and is easier to grow than native milkweeds. Unfortunately, this plant harbors an amoeba which infects the monarch butterflies

that feed on it, causing misshapen wings and other “birth defects.” Since the flowers bloom year around, they fool the butterflies into thinking it’s breeding season, and they fail to migrate as they should. As if the monarchs didn’t have enough strikes against them.

Beginning in 1927, tung production occurred from Texas to Georgia and south into Florida and the Gainesville area. In 1969, there were 13,961 acres of Florida tung trees. Just north of Gainesville, Brooker was the site of a tung plantation.

Cultivated primarily for their seeds, tung trees have also been used as landscape ornamentals. They have “naturalized” in north and central Florida and other Gulf states, spreading by seed and suckers from underground stems. Their ability to grow in a wide array of environmental conditions makes them a successful, if slow, invasive. Tung trees are listed as a Category II invasive species, invading forest edges, right-of-ways, and urban green spaces in the panhandle and Suwannee, Alachua, Marion, and Levy counties. Did I mention this plant is toxic? A single seed can kill a human.

Today we are more aware of the risks posed by imported plants and animals, but we must remain vigilant. Education, awareness, and coordinated effort is required to preserve the delicate balance of Nature and a sustainable world.

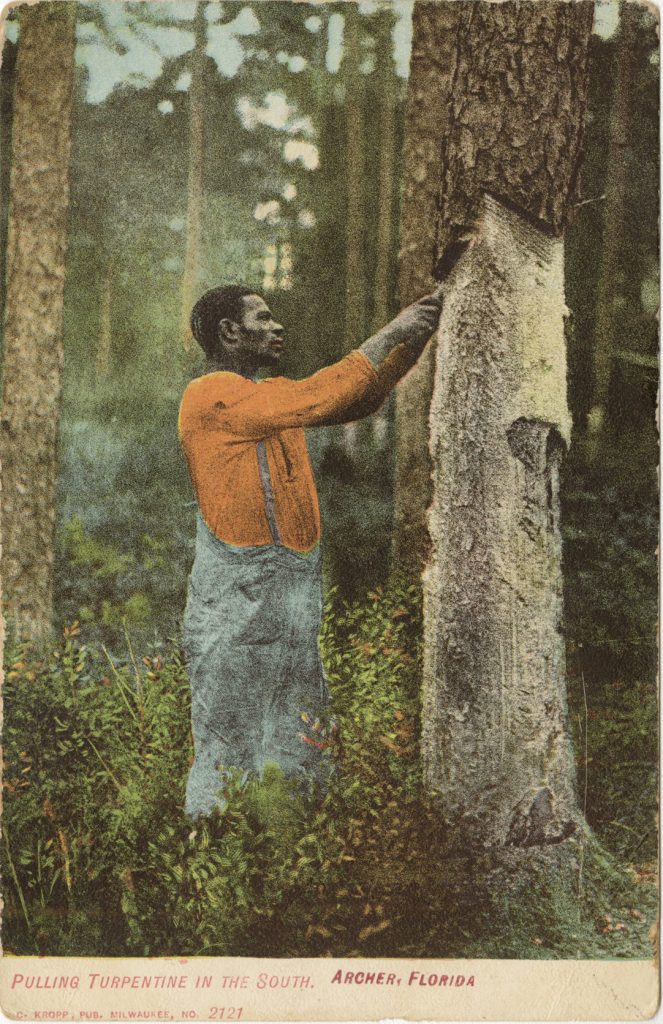

- Pulling Turpentine in the South, by Michelle Dunlap

My name is Kemet, but my friends call me “Tree” because I’d been working 19 years pulling turpentine pitch from the Florida-Georgia border down to Ocala. I was 13 the first time, as my Uncle Sammy “supervised” me while he also was pulling. Only difference was, he could pull even while stumbling three sheets to the wind, whereas I hadn’t yet touched liquor. We both got our jobs done, I had watched him enough times, and could do it myself although I was a lot messier at it than he was. It is dangerous work though, you could get deeply slashed, burned, or fall from very high heights, that is, if the bosses don’t kill you first. If you ever see a tall strong pine that has what looks like a wide river of missing bark running longways down its side, that’s an old tree from the pitch-pulling days—before they came up with all the new technol’gies for sealing up holes in boats and other things needing protections from the harsh elements found in salt water.

Uncle Sammy died at the very same age I am right now, 32. Can you imagine, dying at 32? Cirrhosis of the liver they said, but it was really facing the daily brutality of this world that killed him. People think that pulling pitch should be easy enough, but down here in Florida, you might’ve well stayed enslaved. Just last week they killed a young man, Martin Talbert, for jumping on a freight train trying to go see his sick mother. The gov’ment, for punshment, beat him with 50 lashes and put him on pitch-pulling, and within two days he was dead from fever. That’s how my Uncle ended up on the line, for petty crimes like vagrancy and jumping on trains. When I turned 13 he asked Momma to meet him with me in hopes that I could help make a few pennies because those in the system, even if for petty crimes, all their money went to the state. Eventually mine did too, after they accused me of stealing pitch. What would I steal pitch for? I don’t have any boats or ropes that need sealing. My God! The gov’ment funnels us into the system because them and the turpentine industry are in bed together, and they can get near-free labor from the prisoners. In one work camp here in Alachua County, 21 laborers were abused and killed, while the gov’ment ruled them all natural causes.

I’ve drawn pitch from that wide river running longways down many a tree. But I never thought that such would be the very last thing that I myself would see. Feet and hands tied, strung around the tree as I face it. My nose buried deep in the wide river of missing bark, I remember how Momma mourned when she kissed me goodbye at 13. The powerful bosses and the gov’ment have decided that I will be number 22 to die of natural causes.

__________

Historical Sources:

https://www.orlandosentinel.com/1993/03/07/lynching-floridas-brutal-distinction/

https://flowriter.net/2018/11/09/the-brutality-of-floridas-turpentine-industry/

https://naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/history-lynching-america

This postcard, printed between 1872 and 1917, required only a 1¢ stamp.

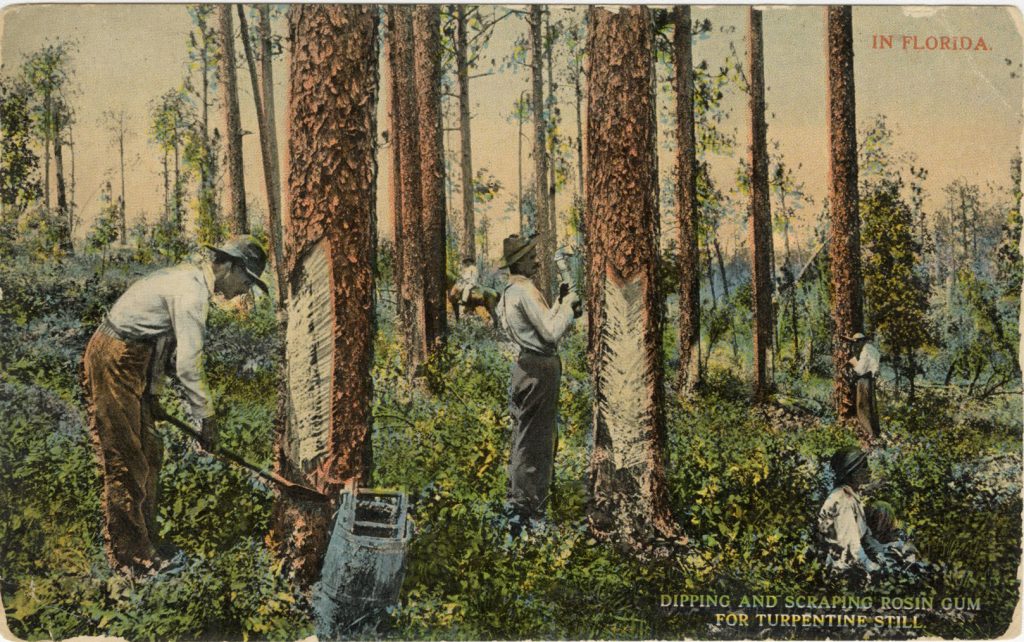

- Tapping Longleaf Pines for Turpentine, by Susie H. Baxter

Men in the foreground are tapping longleaf pines for sap to be distilled into turpentine. If you look closely near the center of the image, you will see in the distance a man on horseback. The rider is likely a guard who carries a gun with which to shoot any worker who attempts to flee.

Convict labor was used in Florida in the late 1800s when turpentine was one of the state’s largest industries, and after the use of convicts was outlawed in the early 1900s, the labor fell mostly to black men arrested for minor crimes and funneled into forced labor camps.1

To harvest the sap, the men used a tool such as a hack to slash strips of bark off the tree’s trunk near its base. Another slash was made from the opposite direction to form a V. The angled cuts resembled cat whiskers, so the scars in the trees became known as catfaces.

The sap oozed from the gashes and ran along metal gutters into a clay cup or a metal box, collected every week or two when fresh cuts were made a half-inch higher. One tree would yield 7-8 pounds of sap per year. Trees could be tapped again and again until workers

could reach no higher on the trunk. Then, cuts were started on another side. This weakened the trees, of course, and caused many to die. The 90 million acres in the American Southeast gradually dwindled to about 3 million acres.

While turpentine has primarily been used as a paint thinner, it and the sap’s by-product gum rosin are also used in numerous products, from floor polish to Crayolas. For centuries, turpentine even had medicinal uses. Old timers were advised to pour it on cuts to stop the bleeding, apply it to rattlesnake bites to draw out the venom, and mix a few drops with sugar and swallow it for the relief of a sore throat, cold, or stomach ache. Today, of course, doctors advise against ingesting any amount of turpentine since it is toxic.2

__________

1https://dunnhistory.com/the-brutality-of-floridas-turpentine-industry/

2https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/is-turpentine-medicine

3Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), USDA

Longleaf Alliance: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o1nSoktY3UY&t=124s